| Dean Park Press is delighted to announce the publication of Gordon Lawrie's first anthology of short stories, Grace Notes. Consisting of twenty standalone tales, many have a musical theme and a fair number feature original music – pop music, folk music, a classical piano piece, an advertising jingle and even a ringtone for a mobile phone. |

|

0 Comments

Not so long ago I read a book that had been given to me by a friend: 'You'll enjoy this, I think.' The friend was right, because I did, a great deal. But I found myself flicking over some of the submissions – all novels, of course – that we've received here at Comely Bank Publishing over the years. Broadly speaking, novels fall into three categories.

1. The Quality Novel. This book is satisfying and well written, with a plot, characters and a sense of time and place that makes the reader feel part of the novel itself. Critics love it, it's entered for literary prizes. 2. The Bestseller. This book makes no claim to be a literary tour-de-force, but aims to please and entertain. It should be aimed at a specific market – which could be the air traveller, Womens' Institute groups, teenage fantasy, chick-lit, or erotic fiction. This book is out to make money. 3. The Cult Classic. This book could be anything. It might not be particularly well written or appeal to a mass market, but if successful it will have a 'following'. Books like these need to become famous for some other reason: perhaps they're made into a successful movie, or are referenced in a TV series, like The Third Policeman in Lost. But don't hold your breath waiting for these to do well. In the old days of the Net Book Agreement, UK publishers could insist that books were sold at the price on the rear cover. It meant they could use the profits from successful books to subsidise up and coming authors, or even academic books. No longer. Nowadays you have to be sure what your book is trying to do. Is it good enough to be a literary classic? Will it appeal to a specific mass market? Or is it just yet another cult novel? Because unless you're a very, very good writer, only a mass market book will interest a commercial publisher. As for the cult novel? Forget it. Self-publish, hope it attracts attention, and don't be too disappointed if it doesn't. Writers tend to forget that time is money. From time to time we're asked to look at submissions from enthusiastic writers who have poured their life and soul into a novel. Sometimes they're just looking for an opinion, but more often than not they hope that we'll say that we'd like to adopt it at Comely Bank Publishing.

But have you ever stopped to think about it from the publisher's viewpoint? Even if your book is any good – and it's unlikely to be more than "promising" to start with – it might not be the sort of thing that the publisher's reader enjoys. Either way, reading your manuscript is most definitely "WORK". Workers rightly expect to get paid. Now think about how long it takes you to read a novel. Let's make it easy, take a short one like F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. That's less than 50,000 words long. Sit down and read it in a day, perhaps? That sounds like 8-10 hours to me. The minimum wage in the UK (from April 2019) is £8.21 so that's just £65.68-£82.10 payment. Bear in mind that's a masterpiece. Yours will take longer. And people who read manuscripts are usually pretty highly-qualified and expect rather more than the minimum wage. Plus they have to make up some sort of report and send a reply to the author. Plus they're entitled to holiday pay and so on. That's why agents and publishers have to be brutal with submissions. Simply to survive, they have to cast aside anything that doesn't grab their attention immediately. And expecting them to do it for nothing, or for next to nothing, is really a bit insulting. You wouldn't. Emma Baird has left Comely Bank Publishing to concentrate all of her efforts on her own personal publishing label, Pink Glitter. As a result we no longer stock Katie and the Deelans (ISBN 9780957352179), which is now out of print. To enquire about obtaining copies of the book, please contact the author herself.

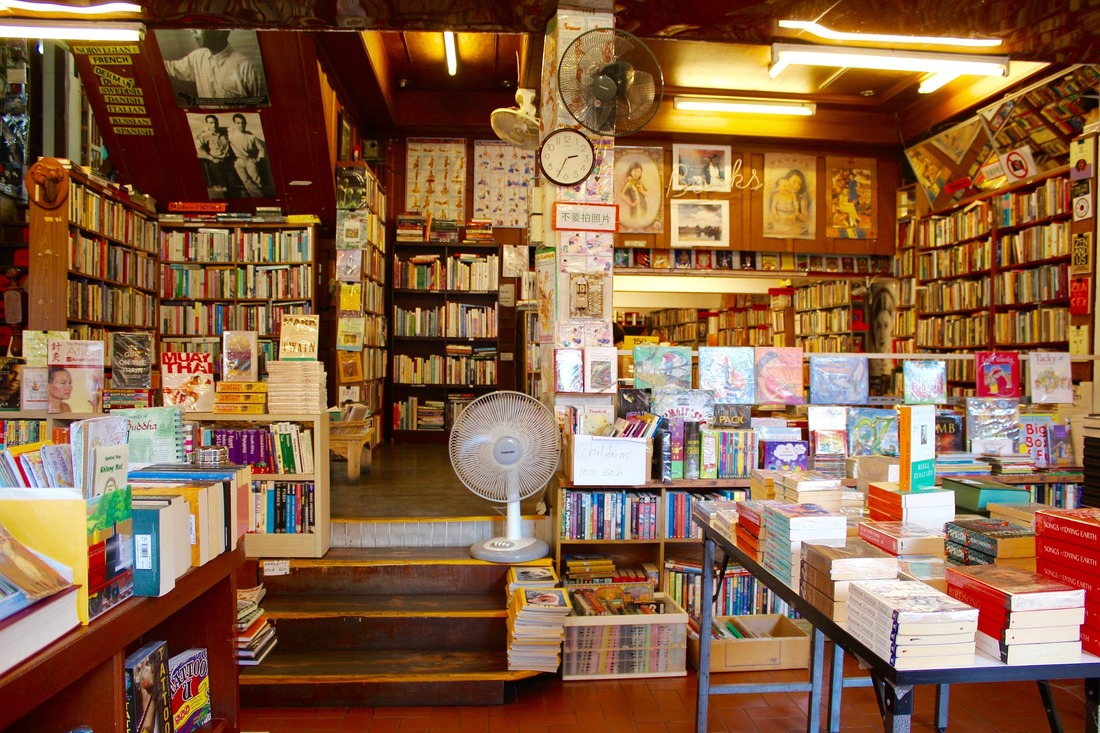

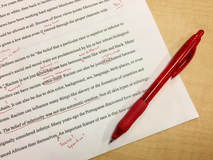

We wish Emma well in her future career.  A writer that I know has just published her third novel. It's great, her best yet. In her case, the main reason that it's so much better is that her plot is better controlled than in her earlier books. It's as though she's had a piece of paper by her side on which she's already mapped out the narrative, like a route marked out on a map. Perhaps she did exactly that. I thought her first book wasn't very well edited, to be honest. A debut novel is often a bit random, lacking discipline, and the author is often too closely attached to it. As a result, an editor's advice given is often ignored, or taken in hurt. In this case I suspect that the editor of her first book simply was too gentle to spell out in words of one syllable just what needed to be done. He wasn't brutal enough. You'll notice that I haven't named the author in case she reads this! But the (de facto) editor of that first book was me, and so... well, the book didn't do as well as the author might have hoped. But her novel was essentially a good one and maybe one day, when she's rich and famous, she'll get the chance to re-write it. In the meantime she dumped me for another editor, someone I think she knew less well and was therefore able to tell like it is. These days I'm much more experienced as an editor and if something needs to be said, it's better said. A poorly-edited book never sells well. Not that the writers necessarily listen, of course, and it's only natural to hear criticism more loudly than praise. But remember that if an editor says a book should be edited in various ways, it also means it can be edited – it's got real potential. If it can't be edited, it's probably only fit for the bin. Gordon Lawrie's editing services are available through his own website.  I've had quite a few manuscripts of historical fiction novels submitted in the last few years. By and large they're well enough written, although all too often the writers get a little too keen to give me a history lecture. As I've said so often before, historical fiction is simply a good yarn set in the past. The essential elements of the plot should work no matter even if set in the present. I understand the appeal of historical fiction for writers. Historical research allows an escape from present-day drudgery, a chance to delve into another world where your boss is non-existent, the latest pressures of work are far away, and the heart can operate at a slower rate altogether. Stamp collecting, golf, chess, yoga and knitting all do the same thing, I'd imagine. But if you set your book in a past era, make sure your research is thorough. There's no excuse, say, for having your central character meet Queen Victoria in 1904 when she'd already been dead for three years. Yet that sort of stuff gets written. You don't have to get it right straight away, but you have to allow your manuscript to be checked for blunders and then be prepared to edit accordingly. I'd call that technical editing*, checking that the details in the background stack up properly. If you were writing a crime novel, or a science-based work, you'd surely let an expert run an eye over it. Historical fiction is no different. You might have researched a period extensively, but a trained historian knows how and where to look to check your details. Get your history right and, like Tolstoy, your novel might one day end up as essential reading for history students. Get something wrong and your readers will end up laughing at you. Because in every field, be it arts or sciences, researchers are known not for their best piece of research but rather for their worst blunder. * I've written about developmental editing and line editing elsewhere. Everyone likes to support their local independent bookshop if they can. They look good, have a nice feel about them when you go in, and generally create a nice vibe in the high street. Big booksellers – Waterstones, W. H. Smith and so on – are the bad boys, undercutting the little shops and putting them out of business. I think that's a fair complaint: the Net Book Agreement did wonders for the UK publishing, especially in supporting new and niche authors.

But readers need to understand what they do when they enter a bookshop. Unless you go in specifically to place a special order for a title, you're going in looking for ideas, for inspiration. The smaller the bookshop, the more likely you are to be given suggestions, have a discussion with the owner or manager, and leave with something tailored to your needs. Great. But that means that your choice is limited, indeed by the very process of passing through the shop's front door, you've narrowed your selection of books to the owner's choice. If the owner doesn't like the book, or has never heard of it, you won't be leaving with it, that's for sure. One or two of the newer independent bookshops in Edinburgh (at least there are some) are really too small not to be guilty of choosing the customer's reading for them. I was in one recently where the owner has no chance of having any book I'd be looking for. But if that's what the customer wants, fine. On the other hand, huge shops like Waterstones carry huge numbers of titles, and a customer who can't find what they were looking for will leave feeling very disappointed. They might not get help, they might not feel particularly valued, but they've a fighting chance of finding the book. It's a difficult balance. And when you throw in the fact that a surprising number of these independents are really disorganised about settling their bills promptly with small publishers, then customers can see that the bigger stores have something to offer, too. Large distributors like Gardners and Bertrams take big cuts of the book prices, but at least bookshops that deal with them do so efficiently. A little money is better than nothing. Even the beast Amazon – which creams off a shocking 33% from the cover price of a book – actually pays over in good time. By contrast I once had to drive a round trip of 50 miles to demand money from a bookseller who had ordered (and quickly) sold two of our books but then failed to pay for a year, ignoring repeated requests. There are good, supportive independents, but at their heart in every case is an individual who is genuinely committed to doing their best for everyone. These people are real unsung heroes. But all it takes is a small change in personnel somewhere and it all goes pear-shaped. In the end, a bookshop is only as good as the person at its heart. Yes, I'm back on that subject again... the amount we lose out of our RRP to other agencies. There are a lot of sharks out there.

It's not really a secret that the standard "bookseller discount" – i.e. profit margin – is 40%. In other words, from a £10 book, the bookseller gets £4.00. Strangely enough, I don't really mind their 40% at all, because they do have to stock the books, pay their staff, fill up shelves and pay for their premises before they get anything back of the other £6.00. A dud book can take up a lot of valuable space on a small indy bookseller's shelf. I DO have a problem with Amazon, though. For the same book, Amazon will take the quite staggering sum of £3.30, even although it does nothing except advertise on its website and check payments are made. That 33% becomes even higher if the book is cheaper, by the way. And then there's postage/distribution. Despite all of my efforts, Royal Mail simply refuses to allow books thicker than 25mm to go as large letters. Instead they have to go as parcels, increasing the charge by almost two-thirds. Anything thicker than 25mm and the book's postage will be £2.85. If my package contains two books, I have to take it to a post office and my local post office manager could not be less helpful. (She insists I wait in a long queue for a proof of postage certificate that I don't need or want.) You'll see where this is going: from our £10.00 book, we get just £3.15. Which has to cover the printing costs, designing the cover, editing, proof-reading... oh yes, and a little for the author. So we've taken the decision to use Royal Mail only for the smallest books, those we can send for £1.74. We certainly can't afford 1st class post any more. For the rest, we've turned to other carriers, not a lot cheaper, but certainly a whole lot more helpful. If you're a small publisher, I'd suggest you think about doing the same. Honestly? Royal Mail no longer deserves your loyalty. Undiscovered Scotland's Review of........................ The Blogger Who Came in from the Cold29/8/2018

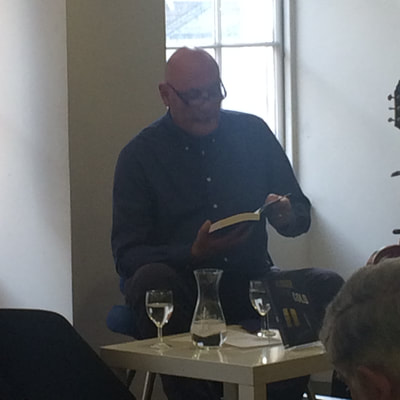

On 3rd August, Gordon Lawrie returned to Blackwell's Writers at the Fringe for the first time since 2013, alongside four fine writers: novelists Jane MacKenzie, Hania Allen and Olga Wojtas, together with poet Rita Bradd. Gordon spoke for a while about his new book The Blogger Who Came in from the Cold and read a short extract. Normally Gordon would then close with music from the new book. This time, however, he talked more about the interaction of music and fiction in his work and sang a new song, The Shores of Caledonia. Here's an excerpt from his performance. If you've signed up to the Comely Bank Publishing newsletter (and just get in touch if you haven't but would like to), the latest one contains a free short story by Roland Tye. It's called Demons, and if you'd like to read it, you can download a pdf from the link below.

I'm suffering from an interesting affliction: novelist's block. Never heard of it? Well, neither had I until recently, when I discovered that I could write almost anything except a continuation of my latest novel. Short stories? Flash fiction? The odd (very odd) poem? No problem. Even the occasional song, believe it or not. But a novel? Nosirree. The keyboard's gone cold. Part of my problem is that I'm easily distracted. Short fiction suits my lack of concentration rather well, although even a decent-length piece can be challenging unless I'm in the right mood. But I probably have enough to publish a collection, even allowing for one or two being dropped out by an editor. The Blogger Who Came in from the Cold hit the bookstores only last week. But while that book had been going through the editorial and cover design sausage machine, I'd been writing its successor... until it hit the buffers. So what next? Ironically I covered this very subject myself in a blog a couple of years ago. But that assumed a general writer's block, not a problem with something specific. I suppose that, in the end, there'll be nothing for it but to lock myself in a room and grind it out. But I also know what that means: it means that I'll have to start all over again once I'm finished. Because a novel must flow seamlessly, carrying the reader along with it. And if it's not doing that for me, the author, it's hardly going to do that for anyone else. Don't expect that new novel any time soon. Gordon Lawrie

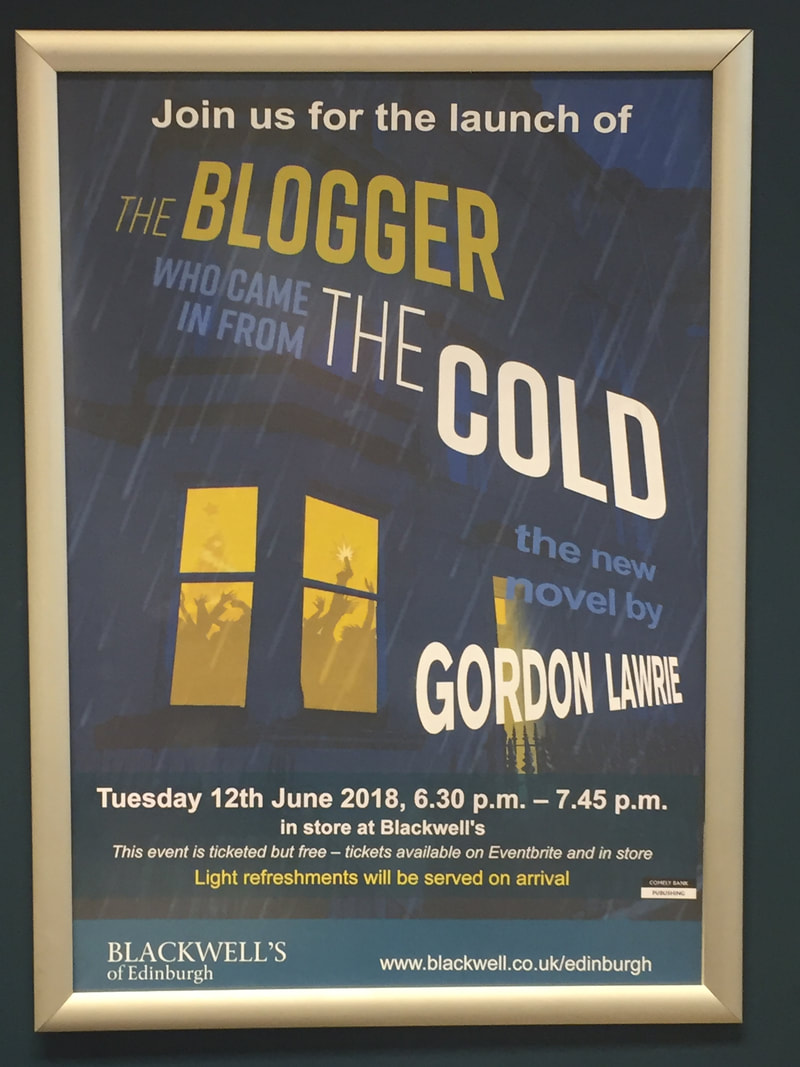

These photos of the launch of Gordon Lawrie's The Blogger Who Came in from the Cold are courtesy of Callum Chomczuk.

Last night saw the launch of The Blogger Who Came in from the Cold by Gordon Lawrie in Blackwell's South Bridge, Edinburgh. Gordon was "in discussion" with the Edinburgh International Book Festival's Helen Chomczuk (although she was anxious to make it clear that her role there is a non-creative one). Helen also happens to be his daughter.

The evening was really well attended. Helen skilfully prised a few nuggets from Gordon, who also read a couple of excerpts and played a couple of snippets of not-very-good (his words) music from the book. Questions followed from the floor to conclude a fast-flowing evening which one observer described as "buzzing". Gordon Lawrie's new novel The Blogger Who Came in from the Cold will be launched (and published) on Tuesday, 12th June in Blackwell's, South Bridge, Edinburgh. There are still tickets available for this event, which is free and begins at 6.30.

The other day a fellow writer got in touch with me. She'd written a story faintly referencing a well-known burger chain. Then, anxious to ensure she was allowed to quote the brand name in her story, she decided to contact the burger chain's customer services department to be sure.

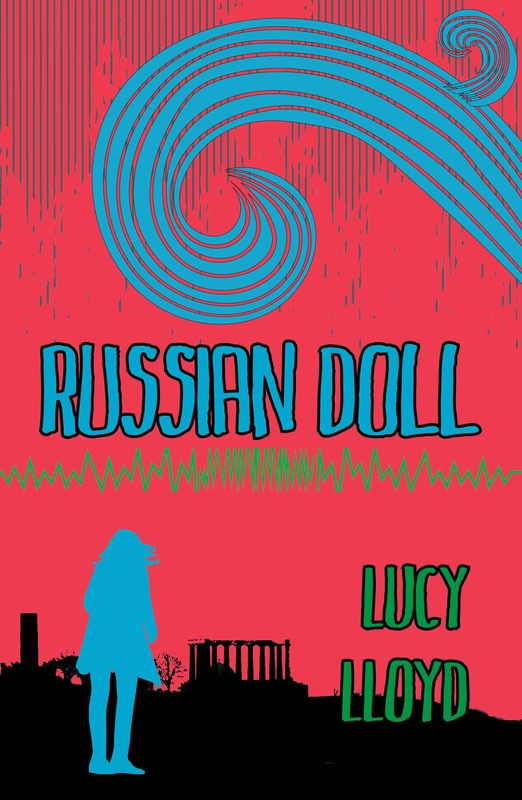

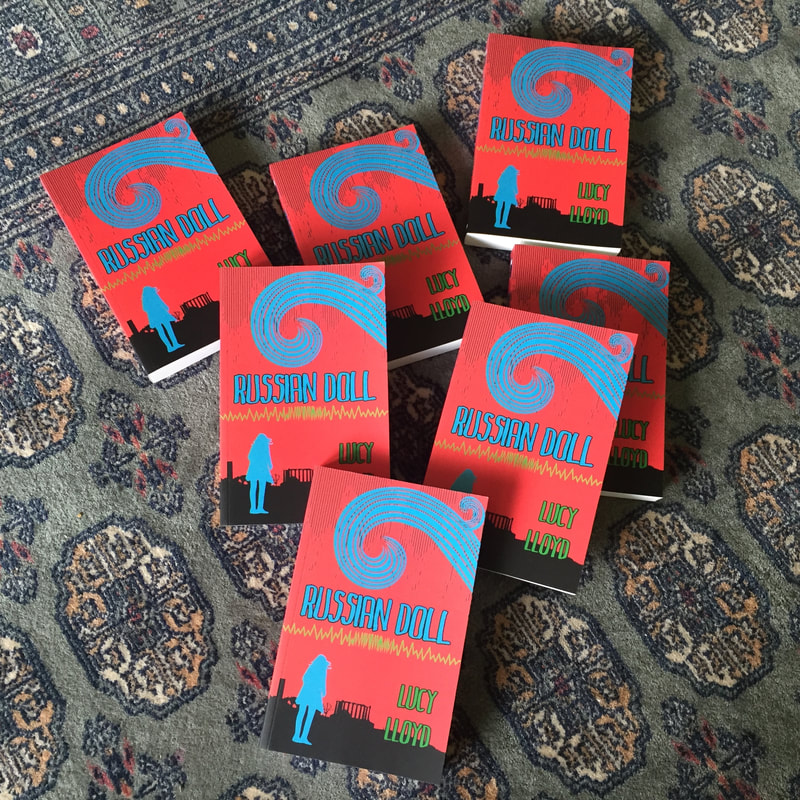

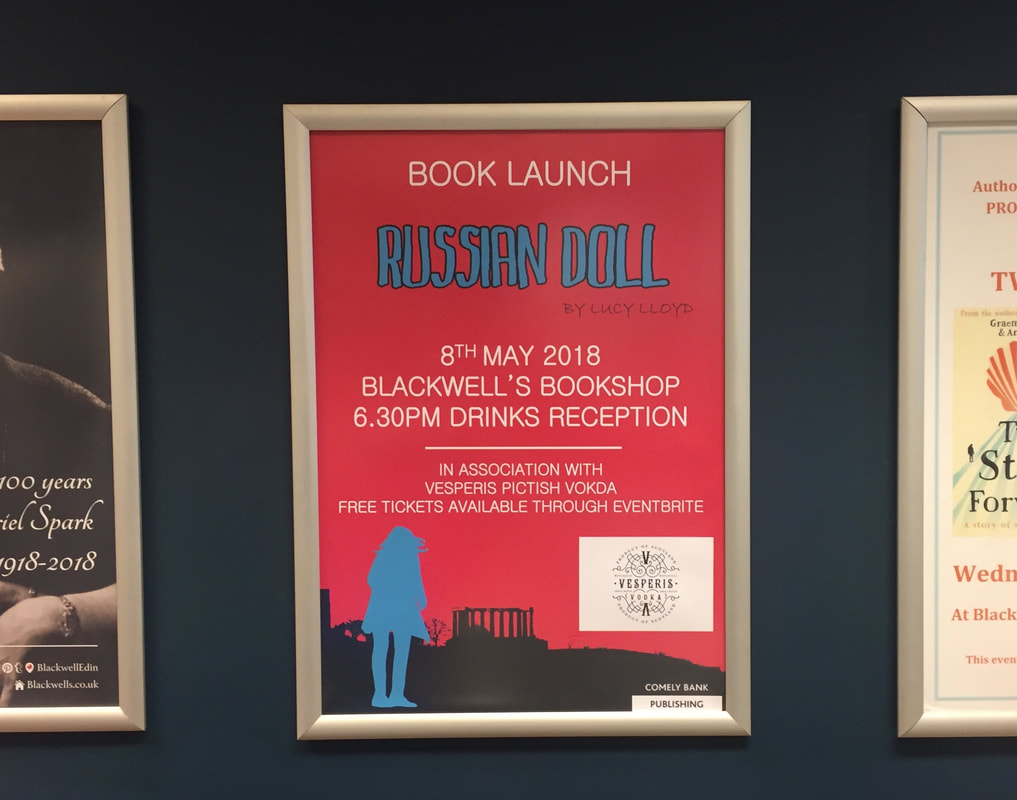

The burger chain (allegedly – you'll understand that I can only quote her version) instead said she could be sued for using their brand name, and demanded to know her name and contact details. Perhaps they threatened to pull her fingernails out and shoot her dog, too, but I've no information on that. Whatever happened, the writer was sufficiently concerned to contact me to ask what to do. I suggested a slight edit, but I honestly don't think it was necessary. I've noticed that North Americans sometimes get a little confused about copyright and trademarks. The author of a work of art – including paintings, sculpture, music, photographs as well as literature – can claim copyright and that he or she wrote it. To claim copyright, all that writer needs to be able to do is to demonstrate that they wrote it first. After that, no one else can reproduce it without the author's permission. However its title can be referred to, and the work can be quoted for the purposes of critical analysis and education research – so long as it's made quite clear who wrote the original. A trademark, on the other hand, is a brand. It can be an everyday word or picture, but even a trademark needs to be able to claim it's unique. Trademarks are registered, mainly to make it easier for big corporations to hunt down other firms who try to steal the brand. Big firms pay agencies to manage their trademarks, and also to frighten innocent callers. That's why a recent case – where a romantic fiction author managed to trademark the word 'cocky' for the titles of her books – is nonsense. US judges aren't doing so well at the moment, but this was a particularly bizarre ruling: allowing a long-established word in the English language to be for the exclusive use of one individual is utterly perverse. Someone will sort that. There are two areas where writers need to be incredibly careful about copyright. The first concerns quoting music lyrics. When I was writing my first novel Four Old Geezers and a Valkyrie, I wanted to have the central character singing some rock classics while bashing an old guitar. Once I discovered the cost, I changed my mind. Quoting one line – just one line, mind you, of the Beatles' song When I'm Sixty-Four costs over $1,000. I changed the story. Note, though, that I can mention the title of the song quite freely. It's also important not to steal images from image stock firms such as Shutterstock, Dreamtime, Adobe and – especially – Getty. These firms can use clever software to trace copies of their work online, so that your ebook cover, say, will be spotted if parts of it match with an image in their library. And they go for the jugular. For £7.00, say, just accept that it'll cost a little to stay onside with the publisher. When you're dealing with the Beatles or Getty, it pays to take care of your fingernails and your dog. Gordon Lawrie  A bit of a storm has been kicking off in the trendy Stockbridge area of Edinburgh. Strictly speaking it's not even in Stockbridge at all, it's in Comely Bank, on the highly controversial site that currently houses Edinburgh Accies' rugby playing fields. Let's be clear about this. This is the very same site that in 1871 saw the first-ever international match, between Scotland and England, and was officially not available for building development at all. It's the same hallowed ground that's been allowed to fall into such disrepair by its less-than-competent owners that it desperately needs to sell land in order to stay alive. And it's the same land that, despite the connivance of the local council, still hasn't yet seen one single shop built. But it's amazing what you can achieve with friends in the right places. Anyway, the fuss began when James Daunt, Managing Director of Waterstones Books, announced plans to open a 'quasi-independent' branch in one of these non-shops under the cloak of "The Stockbridge Bookshop". Daunt said it would be 'a tad smaller' than its biggest Edinburgh branch in Princes Street. Still pretty big, then. That evoked an understandably furious response from Stockbridge's one existing independent, Golden Hare Books, who claimed that Daunt was cheating on a promise not to open bookstores in competition with little independents. In turn, Lighthouse – Edinburgh's self-styled left-wing bookshop on the Southside – issued a predictable rallying call for Edinburgh's citizens to overthrow the Darth Vader of the book world. Arise, ye starving reading classes. Personally I struggled see what the fuss was all about. Waterstone's has no means of filling the shelves of its branches – 'independent' or otherwise – except through its Hub and central suppliers. You're a small publisher and want to sell your books in a few selected local Waterstones branches? Whistle. Waterstone's so-called independents will just be selling the same best-sellers as all the other Waterstones. Along the road (genuinely) in Stockbridge are two real powerhouse charity shops that sell books. They have nothing to fear from a Waterstones, to be honest, and in any slugfest, they'll crush Daunt's newcomer. And here's a strange thing. When that little independent bookshop The Golden Hare opened five or six years ago, there actually was a Waterstones branch almost exactly the same distance away – in the other direction, in George Street. The little bookshop wasn't bothered then. Independents like The Golden Hare, Lighthouse and the excellent Edinburgh Bookshop prosper because locals support them through thick and thin. The Edinburgh Blackwell's brilliantly balances that independent feel with the buying power of a UK chain by focusing on niche markets, such as academic and Scottish-interest work that Waterstones has no idea how to market. So what we have is a number of parallel markets, each being served by different types of bookstore: tiny independent, charity and second-hand, niche, and megastore. I reckon this new bookstore will only be a threat to other Waterstones, at least once everyone's initial curiosity has settled down. Meanwhile, all the other booksellers have garnered some free publicity by kicking up a storm about it. Whatever, this morning it seems that Golden Hare is claiming victory: the new shop is now to be branded as a Waterstones after all, not as an 'independent'. Well done them. Would somebody like to explain to me how that makes a blind bit of difference? Lucy Lloyd's debut novel Russian Doll got off to a flying start last night at Blackwell's branch in the South Bridge opposite Edinburgh University's Old Quad. In a very informal discussion before a healthy audience, the Scotsman's Jane Bradley skilfully steered the author towards opening new light on many of the book's aspects.

Set in an imaginary post-independence Scotland experiencing a soft Russian invasion, the central character of Russian Doll is Anna Aitken, a producer for the newly-created Scottish Broadcasting Corporation. As a former BBC radio producer herself, Lucy Lloyd admitted that she drew on past experience for her descriptions of the internal workings of broadcast media. She also admitted that she admired Anna for her spikiness, but that she wished she had more of her courage. With her husband sitting in the front row, she neatly ducked the question from the audience on whether she herself would have found the male lead character attractive! Lucy gave a couple of readings, and afterwards there were many questions from the audience. That the audience had enjoyed their evening was even clearer when it became apparent that most of the "books for sale" had gone in no time. Perhaps it also helped that there was some free Vesperis vodka to try (the Russian link) both before and after the event! Lucy Lloyd's Russian Doll is priced £9.99, from Blackwell's or any other good bookshop, or from our own website. Lucy Lloyd's novel Russian Doll hits the bookshelves today. Set in a post-independence Scotland facing a soft invasion by Russian, the book is a political romantic thriller. Anna, the central character, is pulled in different directions as she falls for a Russian diplomat.

It's a great read, and is available at good bookstores near you from today. Or order it direct from us. The book launch is in Blackwell's, South Bridge, Edinburgh, from 6.30 to 7.45 – free but ticketed at Eventbrite. Come and hear/see/meet the author and get your copy signed! Recently, one of our books was returned damaged in transit by a leading distributor. The firm – which we'll not name, that wouldn't be fair – made a bit a mess of things, but I'm not complaining about that. It deals with thousands of books and orders every day and everyone makes mistakes.

But what emerged out of the whole process was that book distributors don't exactly rush to get your books out to you. It took ten days to tell us that the book was damaged, and everything is sent by second-class post. That's fine. Distributors have to think about their margins, and if they can save a little by using slower postage systems then they're entitled to do that. Likewise, there's little point in us using first-class post to send books to distributors. Our margins are small enough. However, if you choose to place your order directly with us at Comely Bank Publishing, we will undertake to send your book to you as fast as we possibly can. (That applies to booksellers, too.) Get in touch by email, or order through our Online Bookshop. Lucy Lloyd's Russian Doll will be launched (and published) on Tuesday, 8th May in Blackwell's, South Bridge, Edinburgh. Tickets for this event are likely to be in hot demand, but they're free. If you want to be there, make sure you book your ticket via Blackwell's own online Eventbrite booking system.

The other day a friend casually mentioned that she was looking for someone to help her prepare her manuscript, CV and proposal letter for sending to a publisher or an agent. I'm assuming she'd been advised to do that, because she said she was looking for someone with 'commissioning editing experience' – the quotation marks were hers. It's not bad advice. Writers should always give their manuscripts the best chance of being accepted. I don't think she was specifically asking me for help. I would have been prepared to help a friend, but if you don't know someone it's quite an imposition. There are firms out there that offer the service, and of course they charge a fee. Here's one example, and you can check their prices for yourself by clicking on the logo. It might seem a lot of money, but consider this: you're asking someone to give up a substantial amount of their time to read a book that, frankly, they might hate. Then they'll have to sweat over your proposal letter to see how to turn your sow's ear into a silk purse. And your CV might actually be rather underwhelming if you're an unpublished author. And you expect a report on your book, too.

OK, so that seems a bit cruel. But I reckon that this firm's prices are pretty reasonable given the number of hours spent reading your book alone. Consider this: how many hours would it take you to read a novel of 100,000 words, say 400 pages? Could you really do it in one and a half eight-hour days? Because any longer means that a £100 reader fee is illegal – it's less than the minimum wage. In practice you'd need to read the book on day 1 and leave the morning of day 2 for the letter, the report, the CV and sending the whole lot back.* Bear that in mind when you send your book to an agent or publisher, too. They don't have time to read all of your book and if it doesn't hold their attention from the off, it's heading for the bin. (Chances are it's heading for the bin anyway because these people are so hard-pressed for time but that's another matter.) Realistically, the first page counts most. Spend time getting that right at least. Get the proposal letter right, and above all make your synopsis short and sweet. Tell the story right through on one side of A4. And don't get too disappointed if they still reject your book. It happens to all of us. And you're dealing with ordinary human beings, at the end of the day. *I should make one thing clear, by the way: I've no idea who "Writers Services" are. Their fees might be reasonable for a decent job, but a decent job might not be what they actually do. I genuinely don't know. If you want to find out something about the quality of their work, I'd suggest you ask for testimonials and get in touch with people who have used them.  The other day one of our authors was abruptly informed that she needed to have Public Liability Insurance to be allowed to give a talk in her local library. "Council rules", she was informed, and to the tune of an eye-watering £5 million, too, and so that was that. I could hardly believe it at first when she told me, but I checked up on a number of websites and, sure enough, they all said the same thing. Now I confess to having a slightly jaundiced view of insurance companies: after all, the more afraid they can make you, the more profit they make. What's going on here is that councils are being required to take out their own Public Liability Insurance, which they do with specialist insurers. These insurers in turn try to wriggle out of their responsibility by saying that it's the guest speaker's job to insure themselves. The council leaders hand down the edict to the rest of their staff, and that's the end of it. Prices paid for PLI vary a lot, from just over £20 to almost £100. The one at £22 will still include a commission for the organisers (these things are simply underwritten) and almost everything else must be simply administration costs. The actual "insurance" portion of the payment must be negligible. Which equates, surely, to the risk. What on earth could possibly happen at an author event in a public library? Could the sound of the author's voice break £5,000,000's worth of windows? Could the snoring of the audience crack the building's foundations? Perhaps a pile of the author's books could topple over and cause injuries so severe that the author gets sued for £5,000,000 damages. (And just to be clear, criminal conduct and defamation are always excluded.) If anyone's got any ideas, please let me know. Meantime, as the author said, "Council rules are rules." |

NewsLatest news from ARCHIVED PostsPLEASE NOTE That links in archived posts may no longer be valid

October 2023

proud sponsors of

Friday Flash Fiction |

||||||||||