Undertaking the task. Before becoming too deeply involved in writing a memoir or autobiography, I advise you to determine why you’re undertaking the task. Perhaps you’re writing it for your family and friends with no expectation of major sales: you simply want to leave them a record of your outlook and exploits.

Then again, if you want to sell a warehouse full of copies, think about whether some subpopulation of strangers will want to buy your book. If you’re not a celebrity, they probably won’t unless it’s beautifully written and expertly marketed. Even then, it’s likely to be a tough sell unless you’re a convict, madam, or escort with an attention-grabbing hook to make you the toast of the latest news cycle. Otherwise, your potential readers won’t be emotionally invested in your story before reading it, and that’s what it takes to generate sales.

Planning. First, you need to decide whether you intend to write an autobiography or a true memoir. An autobiography is a life story from beginning to end, whereas a memoir is a selective set of autobiographical sketches that focus on certain aspects of one’s life. I first intended to write a memoir that concentrated on single decade in my life—1966 to 1975. But as the manuscript (MS) took shape I realized that to get the story told, I needed to write a hybrid genre that also related a few adventures from my earlier life and several more recent episodes.

Since 1975 I’d amassed 110,000 words of autobiographical sketches recounting memoires from my early life to more recent stories. I’d written these out of chronological order, in various styles, and at varying levels of discipline, detail, and quality.

Some of these fragments were epistolary—emails I’d written to friends—and some were written versions of tales I’d told people countless times over drinks. I thought the book would write itself it in a matter of months—a simple matter of organisation and editorial polish, right? Instead, the task turned out to be daunting. I struggled mightily through more than three years of false starts, rewrites, and edits before putting together the book I was happy with.

Organising. I assessed the mixed bag of material I had to work with. Unfortunately, I had not developed any particular theme, structure, story arc, cast of characters, or outline to follow. I decided to present my chapters thematically and chronologically within each theme, which seemed reasonable at that stage.

Decide what the memoir is about and state it as part of your short pitch. That’s a difficult but good thing to do before you invest too much time in your project. For example, I decided my memoir was about the baby boom generation in America; unresolved psychological conflicts; how I made a living in spite of myself; and how my health rapidly degenerated at an early age.

Beta readers. After writing, editing, and proofing what you consider a completed MS, submit it to a group of beta readers for their input. Ideally, betas are a half dozen avid readers and critical thinkers whose judgement you trust and who represent your expected readership as well as multiple genders and sensibilities. Tell them to focus on the MS as readers rather than editors—that you intend to hire a professional editor after you incorporate their suggestions. However, invite them to mention needed edits or even use “track changes” in the document.

Tell your betas you’re looking for honest feedback and that you’ll not be offended by critical comments. Send them detailed instructions for suggestions on aspects of the MS such as organization, pacing, flow, themes, character development, believability, book and chapter titles, dialogue, and additions or deletions.

What did my betas do for me? They disabused me of my brilliance. I had organized my book thematically so that I could begin with a hook and then jump into the more interesting portions of the story. The overarching criticism I received from every beta reader was more or less as follows: “In its current form, the MS is choppy. While you tell the story chronologically within thematic chapters, you bounce back and forth in time, making the flow disjointed.” This comment, which I took on board, required I virtually start over. However, it helped me produce a much-improved product. I addressed all the other comments, there were many, as I went along.

Selecting an editor. Some try to make do without an editor, either out of arrogance or to save money. But all writers, no matter how skilled and meticulous, have blind spots when it comes to their own work. Everyone needs an editor.

We've all heard about levels of edit. At the high end, some editors perform ghost writing, which may be appropriate if the writer brings a story to the table but lacks writing skill. We can classify levels of edit as developmental, content, or substantive edits; copy edits; line edits; even proofreading.

Rather than hiring a separate editor for each purpose and paying each separately, hire a single, competent editor who will provide one stop shopping. I see no reason why a strong, developmental editor—one who will work on content, structure, and characterization—cannot also perform copy and line edits. Developmental editors often offer ghost writing and rewriting, services that should be used with the realization that they change a writer’s voice.

I recommend corresponding with at least six editors before entrusting your MS to one. You will be working closely with this person for a significant period and entrusting your book to them. You’ll need to make sure not only that you can afford the editor, but also that you’ll be compatible and that you share the same expectations of the level and type of work to be performed and schedule for its completion.

After internal and external book design, you can go back and pick up another final proofing pass with someone other than your editor to get another set of eyes on the MS.

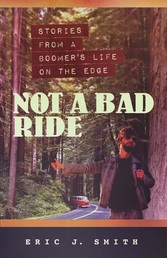

You can buy Eric J' Smith's book Not a Bad Ride on Amazon here. The book is also available on Kobo, iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed